This week’s blog draws on the Gospel readings for the 6 January (Matthew 2.1-12) and for 7 January, the Feast of the Baptism of Christ (Mark 1.4-11).

Clare Amos

Director of Lay Discipleship; Clare.amos@europe.anglican.org

I have never been ‘efficient’ at taking down Christmas lights and decorations by Twelfth Night. I was relieved when some years ago I discovered that an alternative ‘tradition’ allowed them to remain up till February 2 and Candlemas. I do generally manage it by then!

So I have felt cheered (and justified!) by the fact that liturgical revisions over the last 30 years or so have encouraged us to see the whole period between 6 January and February 2 as an ‘Christmas/Epiphany season’, rather than considering Epiphany as a ‘pin-point moment’ concluding on January 6.

This also enables us to have a wider understanding of ‘Epiphany’, a word whose basic meaning is something like revelation/manifestation/shewing.

In Western Christianity traditionally Epiphany or Twelfth Night commemorates the arrival of the three wise men (later often described as ‘kings’) at Jesus’ crib. In parts of western Europe the day is at least as significant as Christmas Day itself – not least as a time for gift giving. As the chaplaincies in our diocese who are based in lands like Spain and France well know, the arrival of the ‘Three Kings’ is often accompanied by colourful street parades – during which sweets are thrown into the crowd which children have the excitement of gathering.

Parade of the Magi in Madrid

Cologne Cathedral, known to some of us, not least because our Diocesan Synod takes place in this city, traditionally contains the bones of the Three Kings. The relics have been located there since the early Middle Ages. A book written by Johannes of Hildesheim in the 14th century to mark the bicentenary of the relics’ translation to Cologne, includes the tradition that the first time the three wise men meet each other before the city of Jerusalem is on the hill of Calvary, where Christ would later be crucified. It is said that although they had never met before and did not speak the same language, they recognised and understood each other and their shared common goal.

The Shrine of the Magi in Cologne Cathedral.

It is however very different in the eastern lands encompassed by our diocese. In Orthodox countries, such as Greece or Russia, the focus of Epiphany is on the baptism of Christ. The day is marked by the blessing of the waters, which can take various forms – often a cross is thrown into the sea, or lake or river, and young men and boys are encouraged to dive in to retrieve it. The ritual not only remembers our own baptisms and the revelation of the Holy Trinity at Christ’s baptism but also expresses the belief that the whole of creation is made holy through Christ.

The blessing of the waters in Greece

The Anglican Common Worship liturgies for the Epiphany season now mark both biblical links – the arrival of the wise men and the baptism of Christ – but they also recall a third ‘manifestation’ of Epiphany – the turning of the water into wine at the wedding feast of Cana.

So, for example, the Eucharistic preface for this season celebrates this ‘glorious’ season in the following words:

All honour and praise be yours always and everywhere

mighty creator, ever-living God,

through Jesus Christ your only Son our Lord:

for at this time we celebrate your glory

made present in our midst.

In the coming of the magi

the King of all the world was revealed to the nations.

In the waters of baptism

Jesus was revealed as the Christ,

the Saviour sent to redeem us.

In the water made wine

the new creation was revealed at the wedding feast.

Poverty was turned to riches, sorrow into joy.

Therefore with all the angels of heaven

we lift our voices to proclaim the glory of your name

and sing our joyful hymn of praise…

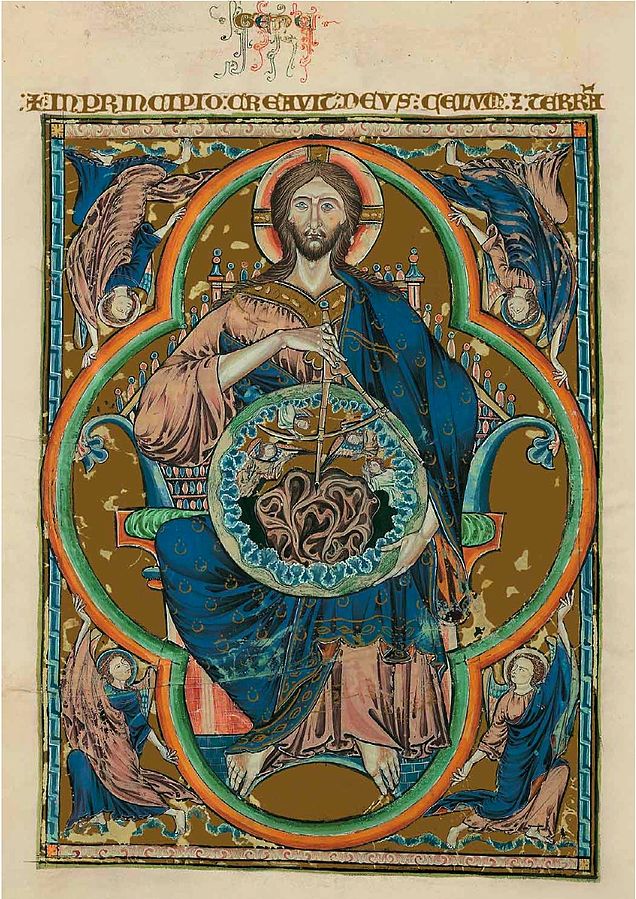

I have used the word ‘glorious’ above deliberately. ‘Glory’ is of course explicitly referred to in the telling of that first sign at Cana, ‘Jesus did this, the beginning of his signs, in Cana in Galilee, and revealed his glory’. (John 2.11) ‘Glory’ in ‘bible speak’ is a way of talking about ‘the visible presence of God’. God is visibly present in all three manifestations of Epiphany: as the wise men ‘worship’ the baby Jesus (Matthew 2.11), as the boundaries between heaven and earth are torn apart at Jesus’ baptism in the presence of Father, Son and Spirit, as Jesus inaugurates God’s long-promised and joyful wedding feast with humanity. As the image in the lovely prayer-poem by Kate McIhagga below picks up, Epiphany is like a multi-faceted jewel, which ‘sparkles’ with God’s light shining towards us from different angles.

But there is something else. I have increasingly come to understand that it is important to see the Christian ‘mystery’ as a whole. Often, partly due to their personal or corporate theology and spirituality particular Christians focus on ‘incarnation’, or ‘cross’ or ‘resurrection’. It is sometimes said that Anglicans tend to concentrate particularly on ‘incarnation’, and that is probably true of some of us, but possibly not all.

The ‘jewel’ that is Epiphany certainly takes seriously the glory of the incarnation, of God being revealed through the human flesh and form of Jesus. But there are also hints in the three facets of Epiphany of what is come later in the story, through the wise men’s gift of myrrh, the traditional ointment used to honour the dead, and through the wedding gift of wine, the symbol of Jesus’ blood that will one day be shed and spilt and shared. Incarnation leads us towards passion and resurrection.

The traditional site of Jesus’ baptism: the lowest point on earth

And the baptism of Christ – which for me takes us to the very heart of what ‘Epiphany’ represents. Latin American theologians have referred to this moment as Jesus’ ‘solidarity dip’ with humanity. The heavens are split open and God comes down to meet with humanity … down… down even into the waters. It is intriguing to realise that the traditional site of Jesus’ baptism in the Jordan near Jericho is actually the lowest point on the surface of the earth (approximately 400 metres below the level of the Mediterranean Sea). But the movement of baptism is one in which submersion is followed by rising up, and it is clear that this down/up movement of baptism has been understood by Christians as reflecting the submersion of Jesus’ passion, followed by the rising of his resurrection. (See for example Romans 6.4).

It is however clear also – not least from Romans 6.3-4 – that we as human beings who are disciples of Christ are also being invited to participate through our own baptisms in the ‘meaning’ of Jesus’ own: we are called to make God present even in the depths, and to share in the movement of passion and resurrection through which Jesus invites us to participate with him in renewing the life of the waters. I enjoy the tradition found in Orthodox iconography of Jesus’ baptism which shows a number of small figures at Jesus’ feet. They represent the ‘demons’ of the unruly waters, now being ‘cleansed’ through Jesus’ actions, to participate positively in their own enjoyment of this new creation.

Byzantine style Fresco of Jesus’ baptism at Rochester Cathedral

Epiphany is indeed a ‘jewel’ out of which the whole of the Christian mystery can sparkle its light, and invite us to share in its radiant spectrum.

Epiphany is a jewel.

Multi-faceted

Flashing colour and light.

Epiphany embraces

The nations of the world

Kneeling on a bare floor

Before a child.

Epiphany shows

a man

kneeling in the waters of baptism.

Epiphany reveals

The best is kept for last,

As water becomes wine

At the wedding feast.

O Holy One

To whom was given

The gifts of power and prayer,

The gift of suffering;

Help us to use

These same gifts

In your way

And in your name (Kate McIlhagga)