This week’s blog focuses on the Gospel reading Mark 13.24-37 to reflect on the ‘Advent time’.

Clare Amos

Director of Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

Clare.amos@europe.anglican.org

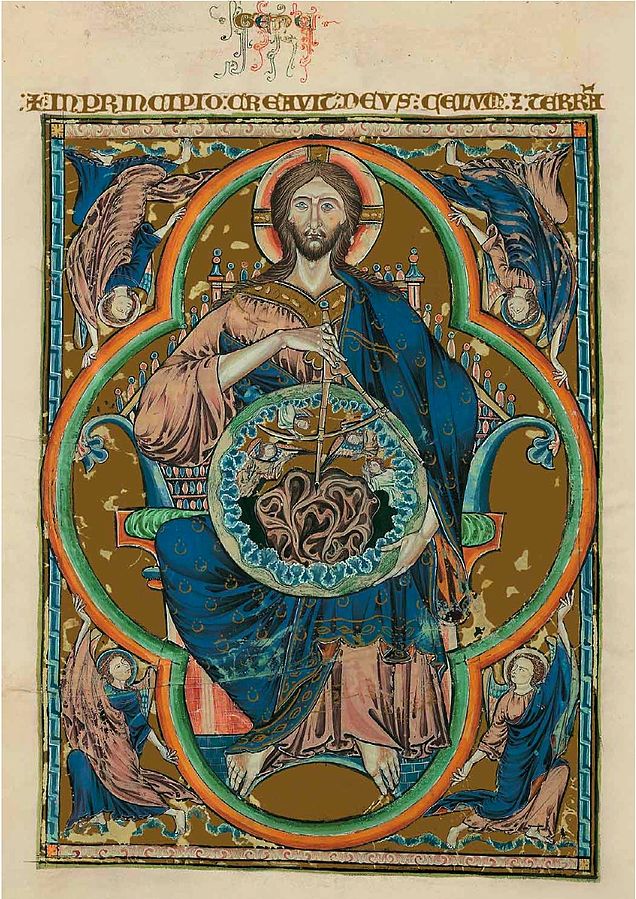

Christ Pantocrator, Toledo Cathedral, accessed via wikimedia commons

What exactly is the season of Advent? J Neil Alexander, a liturgical theologian from the United States poses the question, ‘Is Advent a preparatory fast in preparation for the liturgical commemoration of the historical birth of Jesus in Bethlehem, or is Advent a season unto itself, a sacrament of the end of time begun in the incarnation and still waiting on its final consummation at the close of the present age?’

Traditional ‘Advent calendars’ with their doors opened one-by-one leading us gradually nearer to the stable in Bethlehem and the birth of a baby on December 25 provide one answer to this question.

The usual readings selected for Advent Sunday in the lectionaries of most Christian Churches suggest the other possibility – linking Advent to the end of time. In the Common Worship lectionary the suggested Gospel reading for Advent 1 is a section of the ‘apocalyptic’ chapter from whichever of the synoptic Gospels will be the ‘lead’ lectionary Gospel for the coming church year – which begins of course on Advent Sunday. Over the next 12 months that lead role is given over to the Gospel of Mark, and so it is Mark 13.24-37 which is chosen as the reading for this coming Sunday.

Apocalyptic is a kind of biblical writing in which themes like cosmic confusion and fear and judgement are prominent. Why do we begin the church’s new year – for that is what Advent Sunday is – with such a focus on the end? Why do we have to hear about stars falling from heaven (Mark 13.25); why cannot we simply read about the friendly star that kindly stood over the manger to point the way for the wise men?

One of the fascinating features of Mark’s ‘apocalyptic’ chapter is the way that it concludes, with the words ‘Keep awake’ (Mark 13.37). The identical phrase ‘Keep awake’ appears in the following chapter, in Jesus’ instructions to his sleeping disciples in Gethsemane. Although Matthew and Luke also use similar phrases in their ‘apocalyptic chapters (Matthew 24; Luke 21) and accounts of Gethsemane the verbal link is not as close as it is with Mark.

So what is Mark’s Gospel seeking to say to us through this repeated ‘Keep awake’?

What I find in the Gospel of Mark to a greater degree than in either Matthew or Luke, is that as Mark retells the story of Jesus’ ministry and passion, he is inviting his readers to share with the earliest disciples of all – Peter and the original followers of Jesus – in following the ‘way’ and joining the journey that Jesus and those first followers had made first in Galilee, and then in Jerusalem, We are not an ‘audience’: rather we are invited to become ‘participants’ in this journey. And though I am reading Mark’s story almost 2000 years after it was first written down, and though my own current context is not one of persecution, I too still find myself treading ‘in heart and mind’ that journey of Jesus which Mark sketched out so vividly for his very first readers – perhaps 35 years or so after Jesus’ earthly ministry .

But, I think, there is one point where Mark seems to break off briefly from telling the story of the ‘original’ ministry of Jesus, and somehow addresses his readers directly, in their own time and context. It is in this ‘apocalyptic’ chapter. Without necessarily denying that ideas expressed in this chapter may well go back to the earthly Jesus, I also ‘hear’ clearly expressed in this chapter the anxieties of Mark’s own contemporaries, his readers who may have found themselves standing ‘before governors and kings,’ and have been brought to trial because of their faithfulness to Jesus (Mark 13.9-11). The tension over the fate of the Temple – its destruction by the Roman army of Titus – whether this was still to happen at the time Mark wrote, or whether it had recently occurred also seems to be alluded to (Mark 13.1. 14).

The repeated ‘Keep Awake’ – uttered to Mark’s own contemporaries at the end of 13, and to Jesus’ first disciples in the following chapter has the effect of ‘bridging’ the thirty or so years between the experience of Jesus and his disciples in Gethsemane, and the experience of Mark’s contemporary readers. Their suffering becomes in a sense a ‘new Gethsemane’. The fact that Jesus’ own Gethsemane experience ultimately leads to life through death can in turn offer hope for Mark’s own contemporaries – and perhaps us too, readers of the Gospel two millennia later.

In turn that surely invites us to reflect on how we – or the New Testament writers think about ‘time’. ‘Time’ is certainly a key concept for Mark; he introduces the public ministry of Jesus with the words, ‘The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand’ (Mark 1.15) . The Greek word used here is Kairos = ‘a point in time’. It does not mean the same as the other Greek word for time, ‘Chronos’, which is used to refer to a period of time. JAT Robinson wrote an excellent little book ‘In the End God’, which deserves not to be forgotten, which explored the difference between these two different understandings of ‘time’ and their implications for us. Advent is certainly a ‘time’ to which time is central. Karl Barth once commented, ‘Whatever other time or season can or will the Church ever have but that of Advent?’

Time: sharp as a knife

In April there is going to be conference to mark the 60th anniversary of the great Toronto Anglican Congress. I am hoping to prepare a paper for it, and so have been reading some of the contributions offered at the original Congress. In the opening sermon offered by Michael Ramsey, then Archbishop of Canterbury, spoke powerfully about ‘time’. ‘Time: we remember that in the New Testament “time” is a terrible word, sharp as a knife. It is Kairos: time urgent in opportunity and in judgment. It is less often the year or the day than the hour or the minute, each hour, each minute being a time of visitation: evening, midnight, cockcrow, morning, the Lord may come. We may be leisurely studying an era, when the divine hour or moment passes and finds us asleep and does not come back again. Yes, it is in places and times that our love of God is tested. “O God, thou art my God: early will I seek thee”.’

Mark’s ‘Keep Awake’ breaks down the ‘normal’ barriers of time and links together as one the past, the present and the future, the experience of the first disciples of Jesus, of Mark’s original readers, and those who read his Gospel today and in the future. We find ourselves joined together in the one time, ‘urgent in opportunity and in judgement’.

As a friend of mine has recently commented, the word ‘Woke’ – which has gained a bad press in some circles – is actually a form of the word ‘Wake’ and is an injunction to stay awake enough to read ‘the signs of the times’ in which we are living!

One key aspect of that apocalyptic language such as we have in Mark 13 is that it offers us a vital reminder that our Christian faith is not just a private or individual affair. Our beliefs and actions can and do have consequences in the social realm, and even at the global dimension. We are not allowed the luxury of believing that the birth of Christ is simply a pretty tale to be celebrated in children’s nativity plays, for the cosmic language of apocalyptic insists that it can and should make a difference to our nations and our world. There is a profound interconnectedness of all things: expressed in part by the frequent use in apocalyptic of the idiom of the world groaning in travail with the birth-pangs of the new creation. Mary’s birth-pangs, Mary’s labour and that of our world (Mark 13.17; Romans 8.22) impinge upon each other.

Hope for a tree?

One of those ‘cosmic’ areas in which the language of apocalyptic can speak to us is that of the wellbeing of creation. This weekend, as I am sure you know, the international climate change conference is happening in Dubai. Increasingly we are becoming aware that this global concern cannot be separated from spiritual decision. Do we really believe that love and self-sacrifice are written into the fabric of the universe? Because that is what, I believe, is necessary if as Christians and as human beings we are going to make a real difference to the story of climate change. The language of seas roaring and earth shifting – characteristic of apocalyptic – somehow constitutes a vital resource that can help us take this concern with appropriate seriousness. And it is telling that in our Gospel passage we also hear about the flourishing of a fig tree (Mark 13.28ff). The tree is a biblical metaphor for hope and possibility in spite of unpropitious present circumstances. There is hope for a tree. The cutting down of trees, as in the world’s rainforests, has become a marker for human despoilment of our world, conversely the planting of trees acts as a sign of human commitment for the future. Do you know the tale from the Talmud? A rabbi was walking down a road when he saw a man planting a tree. The rabbi asked him, ‘How many years will it take for this tree to bear fruit? The man answered that it would take seventy years. The rabbi asked, ‘Are you so fit and strong that you expect to live that long and eat of its fruit?’ The man answered, ‘I found a fruitful world because my forefathers planted for me. So I will do the same for my children.’

On Advent Sunday we are called to wake, and wait, and watch, and wonder that the baby so shortly to come to us is not simply part of our world’s past but also of its future. We are called to make ready his way, but will his way find us ready? Will we find within the rhythms of nature at this time of the year, with its dying and hope of new life, and its radiant but sometimes hidden beauty, God’s word to us? Rowan Williams stunning poem ‘Advent Calendar’ accessible here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IQBPBhQCsxE offers us both hope and challenge.