The contested vineyard 2

Given its three year cycle, in October 2020 the Common Worship lectionary readings Isaiah 5.1-7 ; Philippians 3.4b-14 ; Matthew 21.33-46. were the same as we will use this coming Sunday, I drew attention in 2020 to some significant questions the readings pose for many of us in Europe, and certainly for me. I revisit (and rework) what I said then, for the questions are not ones that have gone away in the interim, indeed in some ways may be even more pressing. However as I noted at the time, it is also interesting that the biblical readings about the care of the vineyard should ‘fall’ so soon after the Season of Creation. Back in 2020 husband, Canon Alan Amos, the most gracious (yet challenging!) of theological conversation partners, wrote a powerful prayer that linked ‘creation’ with the main thematic focus of the blog. This time I use Alan’s prayer to ‘introduce’ the blog.

Clare Amos, Director for Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

clare.amos@europe.anglican.org

Lord, you are our gracious landlord

we the tenants of your land-holding the earth

there is room for all of us as those

who care for your creation.

We like to think we own the plot,

as Christians we can dispense your salvation

to the world

and yet we cannot;

we can point in your direction

and then to our surprise

see many others, from here and there

showing us their signs of faith;

The vineyard is yours, and ever shall be;

you have not turfed out others to bring us in;

for you are the generous host

and at the end of the day

the feast of plenty will provide for all

who wish to come. (Alan Amos)

In view of my own background and professional interests inevitably I read this week’s lectionary passages while reflecting on the topic of Jewish-Christian relations. The readings force us to address an issue that Christians in Europe simply cannot avoid, namely the relationship, both theologically and practically, between Christianity and Judaism. In fact at the present time we are in the most significant part of the Jewish religious year, what are called the ‘High Holy Days’, in which our Jewish brothers and sisters are now celebrating their harvest festival of Sukkot (Tabernacles/Booths) having recently kept both Rosh ha-shana (New Year), then Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement)

The lectionary Gospel (Matthew 21.33-46) is Matthew’s version of what is generally called ‘the Parable of the Tenants in the Vineyard’. It also appears in the Gospels of Mark and Luke, but if anything the version in Matthew feels harsher, in particular because of the comment, ‘Therefore I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken away from you and given to a people that produces the fruit of the kingdom’ (Matthew 21.43) which does not appear in either of the other Gospels. The ‘you’, in that sentence appears to be the chief priests and Pharisees, in other words, key representatives of the institutional Judaism of Jesus’ day.

You cannot read the New Testament without realising that a key ‘puzzle’ in the minds of many Christian disciples in the half century following on the earthly life of Jesus was the question as to why many, indeed most, of Jesus’ fellow Jews had not also seen him as their Messiah and Saviour. The earliest disciples were themselves Jews of course, and for them that ‘puzzle’ was mixed up with their own loyalty and love for their Jewish heritage. Paul, in fact, seems to be wrestling with this issue, in the passage from Philippians selected for this week (Philippians 3.4b-14) – seeking to hold together his Jewish identity, of which he was clearly proud, alongside his knowledge of Jesus Christ. In Romans 9 – 11 he addresses the issue more extensively. Even though, fairly quickly, the majority of the Christian church became people of Gentile origin that fundamental question did not go away, though perhaps that earliest sense of acute personal wrestling and angst became less pronounced among Gentile Christians.

By the end of the first century AD what is often called ‘the parting of the ways’ between Christianity and Judaism was well in train. After the war between the Jews of Palestine and the Romans c 70 AD which led to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Judaism too was seeking a renewed sense of self-understanding. The dating of the various Gospels is a matter of (considered) conjecture, but at least some of them probably date from the period after 70 AD when the attitudes of both the Jewish and Christianity communities towards each other were hardening.

The parable of the tenants in the vineyard, at least as it is recounted in the Gospel of Matthew, seems to reflect this context. It is easy to read it, and it may well be that the author of the Gospel intends us to, as suggesting that the role that ‘official’ Judaism had had in God’s purposes had been taken away from it, or ‘superseded’ – by Christianity. Perhaps it was sometimes too easily forgotten that, as is implied in Isaiah 5.1-7, ‘the Song of the Vineyard’, the Old Testament ‘thematic’ reading for this Sunday, God most chastises those whom God most loves. The idea that Christianity had replaced Judaism, formally known as ‘supersessionism’ or sometimes ‘replacement theology’, became very wide-spread in Christian history, especially after the establishment of the Christian Empire under Constantine. For many – perhaps most – Christians until very recently, their affirmation that God had chosen the ‘Church’ for his purposes, became one side of a coin of which the other side was the assertion that the ‘Synagogue’ and the Jewish faith had no longer any part to play – it had been ‘superseded’.

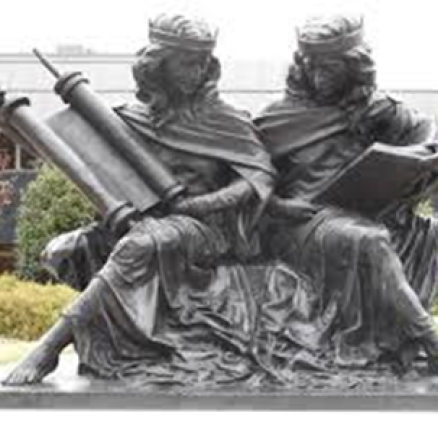

In medieval Europe this was sometimes depicted in art by contrasting pictures or statues of a triumphant Ecclesia (Church) and a downcast Synagoga (Synagogue) – see below. Such depictions hint at the dangerous practical consequence of this teaching of ‘supersessionism’, which proactively encouraged discrimination, mistreatment and all too often violence against individual Jews and particular Jewish communities. In many of our lands of Europe there are notorious examples of such attacks in the Middle Ages. But of course, as we know only too well, anti-Judaism and antisemitism in Europe did not die out several centuries ago. It deeply and horrifically scarred the twentieth century. In fact it still continues today. During the COVID period there were examples of antisemitic lies on social media which suggested that Jews bore responsibility for the spread of COVID-19. In response to the negative medieva portraya of synagoga and ecclesia, St Joseph’s university in Pennsylvania in the USA has produced a modern portrayal which depicts Judaism and Christianity as two euqal and loving sisters. This is used as the illustration at the head of this blog.

Medieval synagoga/ecclesia Notre Dame de Paris

Over the last 20 years in my interreligious work I have enjoyed engaging with Jewish friends and colleagues both professionally and personally. I have been privileged to be part of the working group that produced a fairly recent Church of England report ‘God’s Unfailing Word’ on Christian relations with Jews and Judaism https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/godsunfailingwordweb.pdf and I have been consulted about other reports. I know that many Jews with whom I engage in dialogue believe that it is vital that the Christians disown ‘supersessionism’, and indeed some churches have formally done so, although I suspect the ‘official’ view at the top may not always filter down throughout all the membership.

I have to say that I find myself torn. I am very aware that the question of Christian ‘supersessionism’ isn’t just an ‘academic’ one, either for Jews or for Christians. It does have practical consequences for how Christians behave towards their Jewish neighbours and fellow citizens. But equally I think that Jews need to acknowledge that asking Christians to disown supersessionism is a ‘big ask’. It is not easy because it is written very deeply into the DNA of our Christian theological structure and it has been the default Christian position for nearly 2000 years. So I react against a glib assumption that ‘ordinary’ Christians can easily jettison such attitudes towards Judaism, partly because I doubt that many of them really have. I see it for example whenever a congregation unthinkingly chooses ‘Lord of the Dance’ as a regular Sunday hymn! (Think about some of its words…!) Nonetheless the development of a mature, healthy and honest relationship between Jews and Christians has potentially positive consequences for the peace of the world, not least the Middle East.

And there are some things that it is helpful to point out. For example that it is important to read the Bible, or even particular books of the Bible as a whole. Take this week’s Old Testament reading, Isaiah 5.1-7, which tells of God’s anger with his vineyard, reinforcing its message with a powerful Hebrew pun: ‘I looked for justice (mishpat) but behold bloodshed (mispah), for righteousness (tzedeqah) but behold a cry (tza‘aqah). Read alongside the Gospel reading it feels as though it is reinforcing a message that the original tenants in the vineyard have been evicted. However the ‘song of the vineyard’ is clearly revisited in another part of the Book of Isaiah, chapter 27, and there the ‘song’ concludes with the promise,

‘In days to come Jacob shall take root,

Israel shall blossom and put forth shoots,

and fill the whole world with fruit’

which seems to suggest a very different picture, and it is right that this becomes part of the Christian interpretation of Isaiah 5 as well.

One last thing, which again reminds us of the ‘Season of Creation’. My husband’s prayer/poem astutely reminds us that when we are thinking about the ‘tenants in the vineyard’ it is possible to ‘read’ the parable in the light of the care by all humanity – or the lack of it – of the whole world in which we live. At the end of a northern summer in which several months have been the hottest on record ‘Gobsmackingly bananas’: scientists stunned by planet’s record September heat | Climate crisis | The Guardian that offers a different, but very important ‘take’ on the parable!