Armenian pottery communion plate made in Jerusalem depicting the loaves and fishes mosaic at Tabgha, Galilee

This week’s blog engages with Isaiah 25.1-9; Philippians 4.1-9, Matthew 22.1-14, three Common Worship lectionary readings suggested or Sunday October 15.

Clare Amos

Director of Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

It feels quite a challenge to offer a reflection for this week’s blog, especially given the circumstances that the world, in particular the Middle East, finds itself in at the moment. My husband and I have long-standing links to several countries in the region and to the people that live in them. Current events inevitably reverberate in my memory with some of the horrors we ourselves lived through years ago. I once read the words of Donald Nicholl, a profound Roman Catholic theologian, who commented (in relation to the situation in the Holy Land), ‘the task of the Christian is not to be neutral, but to be torn in two.’ I can honestly say that ‘torn in two’ is how I personally feel at the moment.

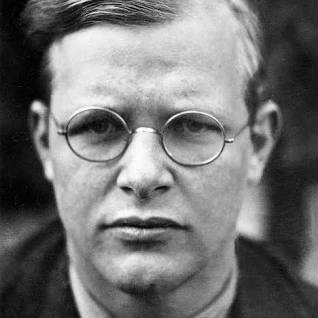

In normal days, I cherish the focus on ‘joy’ and ‘rejoicing’ in the Letter to the Philippians, which reaches its zenith in this week’s selected passage Philippians 4.1–9, ‘Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, Rejoice’. But I am having to work fairly hard on ‘joy’ just at the moment – it doesn’t seem quite a natural or appropriate emotion in the present days. So I remembered the words of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who himself reflected on ‘joy’ in the most appalling of personal circumstances:

‘Gratitude transforms the torment of memory of good things now gone into silent joy. One bears what was lovely in the past not as a thorn but as a precious gift deep within, a hidden treasure of which one can always be certain.’

It is of course salutary to remember that it is likely that Paul penned his ‘joyful’ letter to the Philippians when he himself was in prison.

Back in the 1980s the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, reflecting on ‘joy’, suggested that it was experienced when we try to hold together realities that can be seen as paradoxical: life and death, weeping and laughter, sorrow and bliss. Something of this is expressed in a powerful extract from For the Life of the World a book written by the Orthodox theologian Alexander Schmemann:

‘From its very beginning Christianity has been the proclamation of joy, of the only possible joy on earth. It rendered impossible all joy we usually think of as possible. But within this impossibility, at the very bottom of this darkness, it announced and conveyed a new all-embracing joy, and with this joy it transformed the End into a Beginning. Without the proclamation of this joy Christianity is incomprehensible. It is only as joy that the Church was victorious in the world, and it lost the world when it lost that joy, and ceased to be a credible witness to it. Of all accusations against Christians, the most terrible one was uttered by Nietzsche when he said the Christians had no joy.’

It is therefore significant that the ‘traditional’ preface to our Eucharistic Prayer includes the word ‘joy’…’ It is indeed right, it is our duty and our joy…’, and then speaks of giving ‘thanks and praise’. The pairing of the word ’joy’ with ‘duty’ should perhaps give us pause for thought.

I don’t find this week’s Gospel reading from Matthew 22.1-14 ‘easy’. It contains difficult ‘notes’ – not least the addition of the tale about the man without the wedding garment – that accentuate the frequent focus on judgement that appears in Matthew’s Gospel. I have to confess to finding Luke’s parallel, in Luke 14.15ff a more congenial read.

But Matthew’s version, which describes the event as a ‘wedding feast’ encourages us towards an important insight. Throughout the Bible a ‘banquet’ is presented as the central image of human life as God wants it to be lived. To quote Alexander Schmemann again, ‘this image of the banquet remains, throughout the whole Bible, the central image of life. It is the image of life at its creation and also the image of life at its end and fulfillment: “… that you eat and drink at my table in the Kingdom.”

The New Testament seems to intensify the image into a ‘wedding feast’ as here in Matthew, or in John’s account of the wedding at Cana (John 2.1-11) or in Revelation’s reference to the ‘marriage supper of the Lamb’ (Revelation 19.9). As Isaiah 25.1-9 suggests this will be a time in the future when God will ‘wipe away the tears from all faces’ (Isaiah 25.8).

Over the years I have found it intriguing to notice how from earliest times the Christian understanding of the Eucharist, has not only looked back (to the Last Supper and the death of Jesus Christ), but has also had a ‘present’ and a ‘future’ focus. The present focus is linked to the building up of the Church community as ‘the Body of Christ’, the future focus sees the Eucharist precisely as being ‘a foretaste of the heavenly banquet prepared for all people’ – to which the biblical texts allude.

It is interesting that there is a first or second century Christian text closely associated with Syria in which the thrust of the Eucharist is future rather than past. That is the Didache. The relevant passage has been paraphrased into a fairly well known hymn beginning ‘Father we thank thee who hast planted’. In this Didache text there is no direct reference to the death of Christ but (as the paraphrased version puts it) it concludes:

‘As grain, once scattered on the hillsides,

Was in this broken bread made one,

So from all lands thy church be gathered

Into thy Kingdom by thy Son’.

Throughout much of Christian history this forward thrust of the Eucharist was lost or minimalised, at least in western Christianity. We owe a considerable debt to the Methodist liturgical scholar, Geoffrey Wainwright, who ‘rediscovered’ it and encouraged wider reflection on this aspect. Now, this forward gaze has rightly found its way back into our Anglican eucharistic liturgies. So, for example, at the service I attended at Worcester Cathedral last Sunday, the post-communion prayer concluded with the words:

‘and here a pledge of future glory is given,

when we shall feast at that table where you reign

with all your saints for ever.’

I think there are ‘hints’ in Matthew’s Gospel that the community for whom he wrote also ‘looked forward’ in their celebration of the Eucharist. It is of course interesting that Matthew’s Gospel may have itself originated in a part of Syria not far from where the Didache was probably written.

So perhaps one way of engaging with this week’s rather difficult parable of the wedding feast is to see it as a reminder that in our worship/Eucharist/Holy Communion we are anticipating that joyous future in which God will invite all people to share in the feast that he has prepared for humanity. That will indeed be a time our duty has also become our joy and when, as the lovely Taize chant puts it, ‘The kingdom of God is justice and peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dToFKnGplc

Yet once we begin to look at the Eucharist in those terms, which pull us from the present towards the future, then we need also to remember the salutary words of the former Jesuit leader Pedro Arrupe, ‘Whenever in the world a person in hungry our Eucharist is incomplete’…

Pedro Arrupe

Thank you Clare…good to have you back.

LikeLike