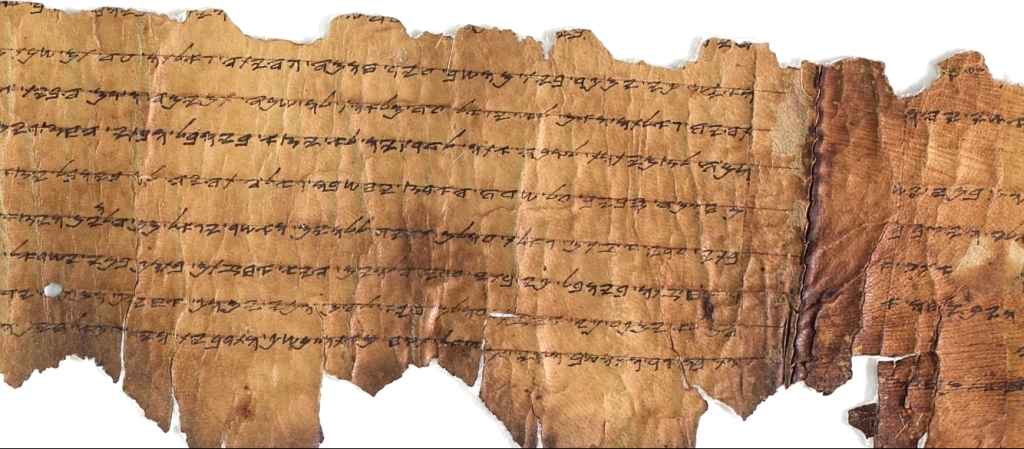

Part of a manuscript of the Book of Leviticus from the Dead Sea Scrolls

This week’s ‘Faith in Europe’ blog focuses on the Gospel reading Matthew 22.34-46, the lectionary Gospel for Sunday 29 October. Current events in the Middle East, as well as the history of religion in Europe, are in my mind as I write it.

Clare Amos

Director of Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

*****

There are two halves to this coming Sunday’s lectionary (Matthew 22.34-46) Gospel reading – each with a question in them. I expect most congregations will concentrate on the first half, and the first question. So will this blog – although I will also draw out towards the end a possible implication of the second question.

The challenge that Jesus is posed with ‘Which is the great commandment in the Law?’ appears in all three Synoptic Gospels although there are minor differences between them. It is however only Matthew who after listing the two commandments – demanding first love of God and then love of neighbour, suggests that Jesus went on to affirm ‘On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets’ – drawing a connection with the reference to ‘the law and the prophets’ in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5.17).

I appreciate the tradition of classical Anglican liturgy of reciting these two commandments in the Communion service – as a kind of preparation for the act of confession. It is perhaps a pity that the practice is not quite as widespread as it used to be. Mind you – in the church I attended as a teenager the vicar considered that merely using these ‘two’ commandments was a concession to human weakness: whenever he had the opportunity he would replace them with the whole Ten Commandments as per the book of Exodus! On reflection I am not sure that he was right – properly observed it is arguable that these two commandments are far more demanding than the Ten.

Over the last 25 years or so I have had the privilege of working in the field of inter faith dialogue and engagement. It is a field which I find fascinating, challenging, vital – and sometimes totally exasperating. Perhaps surprisingly, one of the results of working in this field is that I have discovered new insights into Christian scripture. And that is true in relation to this week’s Gospel reading.

One of the criticisms that is sometimes made of inter faith dialogue, is that it is largely Christians who make the running, and take the initiative in this area, rather than ‘other faiths’. That might have been true 25 years or so ago, but I think that in the last 20 years the picture has shifted. One of the inter faith initiatives that caught wide public imagination is A Common Word. Published in October 2007 A Common Word was an initiative of Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad of Jordan working with a group of Muslim scholars from the Middle East and elsewhere. I have had the privilege of participating in several significant inter faith meetings in which A Common Word provided the basis for our discussion. The document was produced as a response to the critique of Islam that had been made a year earlier by Pope Benedict in a talk in Regensburg in Germany. It takes the form of a letter addressed to Pope Benedict and other high profile Christian leaders. You can find a copy of it here. The ACW Letter | A Common Word Between Us and You The central thesis of A Common Word is that both Muslims and Christians hold in common two important guiding principles: that we are both called to the Love of God, and the Love of our Neighbour. In turn this can provide a basis for Muslims and Christians to work together for harmony in our world. A Common Word then seeks to illustrate this point from both Muslim scriptures (the Qur’an) and Christian scriptures (the New Testament). Not surprisingly, the primary Christian scriptural reference offered is this week’s lectionary Gospel about the two great commandments (and its parallel in the Gospel of Mark).

And the use of this passage in A Common Word led me to reflect more deeply on it, both in terms of our Christian self-understanding, and also what we bring to the table of dialogue with Muslims.

Briefly, I think there are two key points that I would want to make.

The first is that when Christians use the phrase ‘Love of God’ – our fundamental understanding is that love starts with God, not with us. Human beings are called to love God primarily because he first loved us. It may not be directly apparent from Matthew 22.34-46, but it is a profound underlying principle for Christian theology, spirituality and ethics.

Such a trajectory is clearly apparent in the Gospel of John and the letters of Paul. Take for example the Gospel of John, in which the word ‘love’ appears a great number of times, more than in the other three Gospels put together. The first time the word occurs is in the iconic passage, John 3.16, ‘God so loved the world that he gave his only Son’… Then beginning with chapter 11 (the story of Lazarus, Mary and Martha), the word ‘love’ splurges all over the pages of the Gospel. But it is made clear that the question Jesus ultimately addresses to Peter – and to the rest of us – ‘Do you love me?’ is posed on the basis that God has clearly demonstrated the sacrificial and costly nature of love in the life, ministry and death of Jesus Christ. Gratitude therefore is the primary driver which must underly the demand ‘you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind’ (Matthew 22.37). I believe that in turn this will affect how we express such love.

The second point is that for Christians, the two commandments, ‘Love God’ and ‘Love our neighbour’ cannot ultimately be separated: the dialogue between them enriches both our understanding of God and of human beings. It is a framework linked to the Christian understanding of the importance of incarnation, of God ‘dwelling’ with humanity: we are required to see the face of God in our brother and sister and even our neighbour. The clearest expression of this comes in the First Letter of John, ‘Those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen’ (I John 4.20). The love of God and the love of neighbour are not two separate and potentially competitive commandments, but complementary aspects of the one reality.

Why is this important? For several reasons, but certainly this, which feels all too relevant at the present time. Namely that so often those who commit acts of religiously based violence do so on the basis of their understanding of the ‘love of God’. They believe that the justification for their carrying out sometimes horrific acts lies in the fact that they are thereby demonstrating their love and obedience towards God. All religions – including Christianity – have been guilty of this at various times in their history. It is a factor in current developments in the Middle East. In such contexts it becomes even more vital to see Love of God and Love of neighbour as two parts of the one reality.

A brief note (as promised above!) about the second question in this week’s lectionary Gospel, a somewhat puzzling challenge offered by Jesus to those he was engaging with. ‘Whose son is the Messiah?’ – challenging as he does so the conventional understanding that the Messiah was ‘Son of David’. Though I am sure that there is more that could be said, perhaps one implication of Jesus’ question is that in Jesus’ understanding of messiahship the traditional ‘boundaries’ dividing God and humanity were being challenged and overcome. That, it would seem to me, has possible implications for any model of messiahship which is military or hierarchical in character.

Loving Father in heaven

Emmanuel, God with us,

Of your goodness

you have given us yourself,

The richest gift of all.

You invite us to seek for you,

In the face of your Son,

Where you have imprinted your likeness,

Made glorious with the wounds

Of suffering and passion. .

Grant us a spirit of generosity,

So that we may be enabled also to discern your features

In the changing kaleidoscope of this world’s need. Amen.