This week’s contribution is offered by Clare Amos, Diocesan Director of lay discipleship and administrator of this blog. She focuses on the lectionary Gospel for this week, John 10.22-30.

As I write this reflection on next Sunday’s readings it has been an abnormally cold and changeable period, both in Switzerland and in several other parts of Europe. Last Saturday evening snow fell quite low on the Saleve – the mini-mountain which towers over Geneva, and a few spots of it still linger. Snow – in May! What is the weather coming to! So I was struck by the opening of this week’s Gospel reading, ‘It was winter’ (John 10.22). It certainly feels like winter here. John’s note about the season acts as a sort of interpretative frame for exploring the passage. Indeed it is fascinating to look at the link between the seasons and key episodes of the Gospel of John: spring/Passover (John 2; 6 and 12 – end); summer (John 4); autumn/Tabernacles (John 7-9) – and here winter. The reality of winter somehow affects the mood of the passage – there is a contentiousness and a seriousness about Jesus’ words. The passage looks towards the discussion about the close relationship between Jesus and his Father which will dominate the Farewell Discourses.

It is not only winter but, we are told, it is the Feast of Dedication. That is the Jewish festival – these days often known as Hannukah (which is basically a Hebrew word meaning ‘Dedication’) which commemorates the re-consecration of the Temple in Jerusalem during the time of Judas Maccabeus, (2nd century BC) after its desecration by the Seleucid (Greek) ruler Antiochus Epiphanes. Symbolic allusions to these events run through these verses, and the following section (till the end of chapter 10). In verse 36 Jesus’ self-description as the one who is ‘sanctified’ or ‘consecrated’ by the Father is intended once again as a reminder that he has replaced the Temple as the primary location where human beings can meet God. But more profoundly the passage teases out the question of Jesus’ personal identity. There were those who were wondering if Jesus was the Messiah (10.24) In the thinking of the time the military leader Judas Maccabeus was seen as a sort of proto-type of the Messiah, who was often understood as a military or political figure. That view was – as we know – something that Jesus’ himself sought to challenge. However the Messiah was seen as human – rather than divine. So the title did not say quite enough about who Jesus fully was. The passage therefore also highlights Jesus’ intimate identity with God the Father, ‘The Father and I are one’. (John 10.30) The Feast of Dedication gave added resonance to this claim – for two centuries earlier one thing that had scandalised the Jewish community was the claim by Antiochus Epiphanes to be ‘equal with God’ – which is in fact a claim linked to Jesus in John 5.18. Jesus’ words therefore would have been very difficult for at least some of his audience to hear.

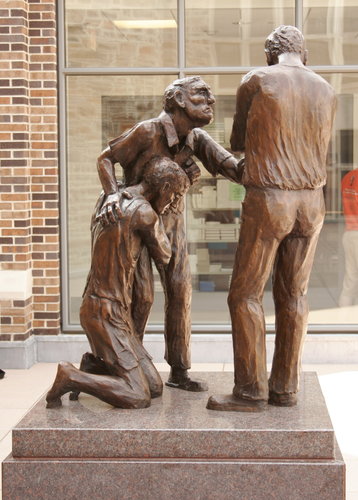

It is not an easy passage: it does feel ‘wintry’ in terms of human dynamics. Perhaps what we need to hold on to most of all however is the fact that we are ‘held’ by Jesus. The assertion that ‘No one will snatch them out of my hand’ (10.28) which has provided comfort for Jesus’ followers in many difficult places and times. The intriguing picture of a sculpture by the Tongan artist Filipe Tohi, on display in New Zealand links the hand of Christ to an anchor stone which holds a canoe safely.