This week’s blog offers some thoughts on the lectionary Gospel, Matthew 18.15-20 and Epistle, Romans 13.8-14.

Clare Amos

Director of Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

clare.amos@europe.anglican.org

Vestibule mosaic, Hagia Sophia: The Emperor Justinian presents the ‘church’

to Mary, the Mother of God.

This week’s Gospel reading, Matthew 18.15-20, in which Matthew explores how to deal with conflict in the life of the church, has significance for me in terms of my personal history in relation to the Diocese in Europe. I moved to Geneva at the beginning of September 2011 to work at the World Council of Churches, and it was a sermon on this biblical text that I heard preached during my first Sunday in the city when I attended Sunday worship at Holy Trinity, Geneva. The choice of that text was following the provision of the Common Worship lectionary, which repeats itself every three years.

The sermon was preached by the then chaplain and it was a good sermon in which he sought to mine the Gospel text for its wisdom on the topic of conflict in church life. In my innocence as a ‘newbie’ I didn’t realise that there was in fact quite a lot of conflict going on at that point in time in Holy Trinity itself and that the sermon was intended to speak into that situation. Happily, the church has moved on since those days, and that in itself has been a learning experience.

Matthew’s Gospel is of course the one among the four that gives most attention to the internal life of the institutional church. Indeed the very word for church – ‘ekklesia’ in Greek – does not appear in any of the other three Gospels. It comes however four times in Matthew, three of those instances being here in chapter 18. The lectionary Gospel for both this week and next week draws on this chapter in which aspects of internal church life and discipline are explored.

One of the interesting features of the Gospel of Matthew is its structure. Embedded within its 28 chapters are five significant ‘teaching speeches’ of Jesus. The number five is unlikely to be accidental – it probably deliberately echoes the five-fold structure of the Pentateuch (Genesis-Deuteronomy). The five teaching moments are the Sermon on the Mount (5-7); the mission discourse (10); the chapter of parables (13); this chapter reflecting on the internal life of the church (18); and finally Jesus’ teaching about the future (23-25). I intend to explore more about this structure next week, but for the moment what I want to highlight is that Matthew’s interest in church life does seem to be part of his wider interest in structure and order.

Where ‘the spirit of the Lord is there is freedom’ (2 Corinthians 3.17) may well epitomise our vision of the ‘ideal’ for the disciples of Jesus, but fairly quickly during the apostolic age it was discovered that to build a healthy Christian community – a ‘church’ – required give and take, constructive agreement and concessions – even, if you want to use the word, ‘laws’. In a sense this is the fundamental story of Christian history over the last 2000 years – how to marry up the glorious liberty of the sons and daughters of God with the need to create some sort of structure that could hold together the followers of Jesus in a way that enabled them to witness to their role as ‘the Body of Christ’. One of the principles to enable this, which Paul sets out in this week’s lectionary Epistle, Romans 13.8-14, where he clearly seems to be drawing on the words of Jesus himself, is for all to be bound by the law of love: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ (compare Matthew 22.34-40)

Different Christian traditions have, over the centuries, sought to offer different answers to this conundrum, of holding together the freedom of individual faith alongside the compromises that Christian community requires. I would suggest that it is characteristic of the Anglican tradition to seek to honour and hold together both ‘freedom’ and ‘structure’. It is actually quite a difficult balancing act to get right, and I suspect that we Anglicans have often failed – but I still believe that there is a glory in accepting the challenge of this via media.

There is of course one additional feature that is seen as characteristic of Anglicanism, or at least of the Church of England. That is the relationship between church and state. Here, of course, we in the Diocese in Europe may have a different perception to those parts of the Church of England on ‘the offshore island’. But even so in many of the countries of Europe we are used to one or other church having a particular relationship with the state in which we live. It adds another dimension to those questions of structure and order.

Which makes it in fact interesting and important to comment on what is not selected as the lectionary Epistle for this Sunday. Over the last couple of months we have been steadily making our way through Paul’s Letter to the Romans. I initially assumed that since we reached the end of chapter 12 last week, the beginning of chapter 13 would be the lectionary Epistle for 6 September. Not so. For the choice of the compilers is to omit the start of chapter 13 and to begin with verse 8. The first seven verses of the chapter, which are omitted, focus on the relationship between Christians and the political state in which they live, in Paul’s case, of course, the Roman Empire. The chapter begins with the injunction, ‘Let every person be subject to the governing authorities: for there is no authority except from God…’ (Romans 13.1). This verse was used in the past to justify evils like apartheid, so perhaps it is understandable that the lectionary compilers chose to omit it. Personally however I feel that was the wrong decision and that this passage needs to be read. There are various competing perceptions expressed in the New Testament about the relationship between church and state. In my view, we need to wrestle with them all, even if ultimately we want to disagree with what they say. To leave out this ‘difficult’ passage – which actually has been very influential in the course of Anglican history – feels rather a ‘cop out’. We cannot understand the history of the Church of England, or indeed the universal Church, without acknowledging the influence of Romans 13.1-7.

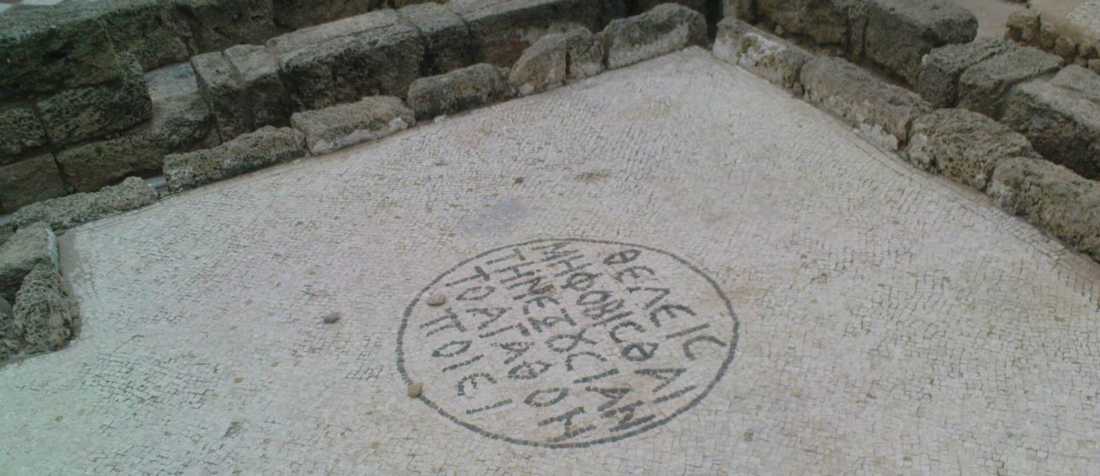

Two interesting pictorial examples of this. Two floor mosaics have been discovered at Caesarea Maritima, the Roman capital of Palestine in New Testament times, and which remained important into the Byzantine period. The text of both inscriptions is Romans 13.4, exhorting the reader to honour the political authority as ‘God’s servant for your good’. It was once suggested to me that the location of the inscriptions might originally have been the library of Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea, the influential bishop and church historian, who was a great supporter of the Emperor Constantine and his policies.

Floor mosaic in Caesarea Maritima, with the text of Romans 13.4

The other picture is a vestibule mosaic in Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (see above at beginning of blog). It comes from the 6th century and depicts the Emperor Justinian presenting ‘the church’ to Mary and Jesus. It makes transparently visible the understanding of the relationship between Empire and Church in the Byzantine period. There is of course a bitter-sweet irony in reflecting on this mosaic at the present time, when it might well be regularly covered over to respond to the new sensitivities associated with Hagia Sophia reverting to its former status of being a mosque. For the very fact that this action has been taken by the Turkish government is in itself a clear mark that the question of the relationship between religion and state is one that will not go away, and which affects many of the religions in our world today.

Today (Thursday 3 September) is the feast of St Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome in the late 6th century, who sent Augustine on the mission to England, and who was influential in shaping the spiritual and political power of the later papacy. At the Eucharist this morning we used a collect honouring Gregory, which speaks into the issues explored above:

Almighty Father, who made thy servant Gregory a bastion of faith in an age of turmoil: Grant that your Church, built upon the sure foundation of the saving work of your Son, may ever be a beacon of hope to the nations, and an instrument of your peace, through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Thank you very much for this, Clare. As always it is extremely interesting.

Patricia LAURIE

LikeLike