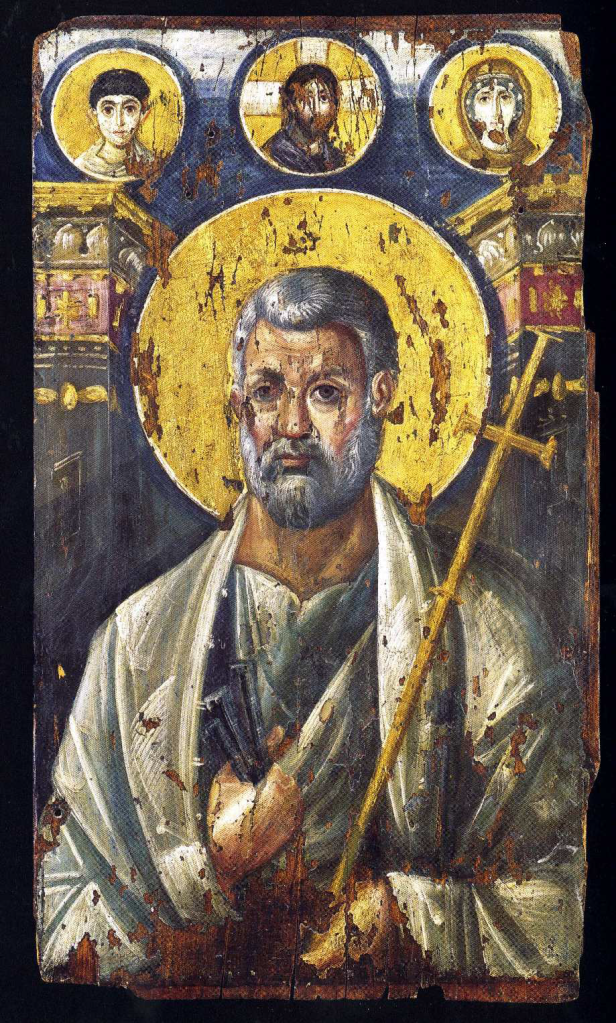

The image above is a beautiful icon of St Peter, part of the icon collection of St Katherine’s monastery in Sinai. It is one of the oldest Christian icons in existence, dating back to possibly to the 5th Christian century. I cherish the humanity that is so evident in the face of Peter. It feels an appropriate accompaniment to this reflection on John 21.1-19, the lectionary Gospel for Easter 3 in 2025. The reflection is drawn from a sermon I preached on this text a number of years ago, initially at the opening service of the General Synod of the Anglican Church in Australia.

Clare Amos, Director of Lay Discipleship, Diocese in Europe

‘And after this he said to him, ‘Follow me’. Have you ever realised that these words, spoken by Jesus to Peter near the end of the last chapter of the Gospel, are the very first occasion in John’s Gospel that Jesus has issued Peter the command – or invitation – to ‘Follow me?’ If you look at the beginning of the Gospel – to the time when Jesus is calling a range of disciples you find that the words are indeed said to others such as Philip – but not to Peter himself. To Peter Jesus rather offers a new name, saying to him, ‘You are Simon son of John – You are to be called Cephas which means Peter.’ But there is no ‘Follow me’. That this omission is quite intentional is reinforced by a puzzling little conversation Jesus has with Peter on the night of the Last Supper, the night before Jesus’ death which runs as follows: ‘Simon Peter said to him, ‘Lord where are you going? Jesus answered, ‘Where I am going you cannot follow me now, you cannot follow me now; but you will follow afterwards.’ Now at the very end of the Gospel it seems is the moment for that ‘afterwards’.

It is all very different in Mark or Matthew. In these Gospels it is at the very beginning of his ministry – as soon as he catches sight of Peter and his brother by the shore of the Sea of Galilee that Jesus calls out ‘Follow me’. They are the very first words Jesus utters to him. And immediately the nets are left and Peter has breathlessly set off on his journey of a life-time.

What a world of difference between those two different moments of ‘Follow me!’ – and Peter’s response to them. The first one is the occasion when Peter impetuously sets off, fired up with excitement – perhaps fishing had been frustrating or fruitless that day or perhaps he was flattered by this sudden attention – so he sets off on a journey with Jesus not really having the faintest clue about where it will lead him. The second ‘Follow me’ is so different. Now he does not know too little. If anything he knows and remembers too much. He remembers that slow, painful process of coming to realise just who Jesus was; and then the even more painful discovery of a Jesus who confounded traditional expectations of how a Messiah should behave. He remembers the running away in the Garden and the shame of that threefold denial. And just in case Peter might have forgotten we have the memory of them etched into the biblical passage from John’s Gospel which we have just heard read. For Jesus’ celebration of breakfast on the beach with his disciples is only possible through a charcoal fire – a charcoal fire that surely recalls a similar one which had been lit that night in the high priest’s house when Peter had said three times ‘I do not know the man.’ And then there is the three-fold question ‘Simon son of John, do you love me?’, reminiscent surely of that same three fold denial. ‘Simon, son of John’, not with the addition of the name which Jesus had once given him, ‘You shall be called Peter’ for in truth so far he has not been a Rock to depend upon. Yet the encounter between Jesus and Peter on the sea-shore looks forward as well as back. So those words, ‘Feed my sheep, tend my lambs’ offer Peter not merely forgiveness, or even a personal relationship with the Risen Lord but an invitation (commission) to a wider ministry and mission. Peter’s future role in the life of the Christian community is being written in to the restoration of his relationship with Jesus. Of course we have read elsewhere in this Gospel just what it means to be a good shepherd, tending to the needs of the flock. We have heard that a good shepherd is prepared to lay down his life for the sheep. And this hint of Peter’s future is then made more explicit, with what seems like a direct prediction of the death Peter will one day meet, caring for the flock that has been entrusted to him in Rome.

And it is only after all this has been said that Jesus can finally offer Peter the challenge ‘Follow me’.

I often think that one way of describing the life all of us have as Christians is that , like Peter, we live between those two moments of ‘follow me. ‘ We stand here having answered the challenge offered by the first, but we are still being made ready to respond fully to the deeper challenge of the second, the one that can only come ‘afterwards’, after we have learned not only to accompany Jesus in his life, but also through his death. How precisely this works out may differ for each of us individually depending on our own personal Christian story – but we are all in some way travelling with Jesus on a journey that began with our response to his first grace-filled invitation, may have taken us through some mistaken twists and turns, but gradually enables us to come to understand more about the nature of our travelling companion on the road, and eventually begin to discern all that it might mean for us, preparing us to begin to make our fuller response. And I think it is important that in John’s account this latter ‘Follow me’ is accompanied by a task, a commission, so that following Jesus does not lead merely to our own salvation but to an engagement in ministry and mission with and for others.

I wonder too whether we can suggest that those two moments of ‘follow me’ may apply not only in the lives of individuals, but also in the life of the Church itself; that here as Church today we are living out our initial commitment to the one we follow – yet it is a journey on which there will be mistakes and much to learn. As Church we cannot properly hear the second ‘follow me’ until we have come to understand what it really means to have the courage to accompany Jesus through his passion and death, and until we have also learned that to follow Jesus may involve us in a sacrificial ministry and mission which will be wider than we might have dreamt of and which may take us down paths we do not know and which, in the words of the Gospel reading, are even places where, humanly speaking, we do not wish to go.

Yet of course it is not only in Jesus’ death that we accompany him – but also in his resurrection, a resurrection which has led to the beginning of a new world, a new creation. Here in John 21 there are echoes of that new creation. Once again God has proclaimed ‘Let there be light’, the sun has risen, the darkness of the night is being dispelled, and the seas are teeming with life. The motif of Jesus offering us a new creation, a new Genesis, which John teases us with throughout this Gospel, beginning with his opening words ‘In the beginning’, comes now to its final fulfilment. Significantly this new creation both recalls of the old – yet also transforms it. For the disciples this means that they have gone back to Galilee, to their old occupation as fishermen, and it is in familiar Galilee that this new creation will dawn, but only when they at last start to see reality through new eyes. Like them we too are summoned ‘to let the morning sun rise on our perceptions of God’s world, to stop looking at things the old way, blundering along in the dark, wondering why we aren’t catching any fish to speak of.’ (Tom Wright)

Do some of you know CS Lewis ‘Voyage of the Dawn Treader’? It is my favourite of the Narnia books. Near the end of the story the children begin to wade through the seas of the uttermost east towards a shore on which they meet a lamb standing by a fire who offers them breakfast. The resonances with John 21 are obvious – and deliberate. But as they are wading through the waters the children look towards the horizon, the place where sea meets the sky. We know that normally this is an optical illusion which will disappear as we get nearer.

But, as Lewis puts it in his story, ‘as they went on they got the strangest impression that here at last the sky really did come down and join the earth – a blue wall, very bright, but real and solid: more like glass than anything else. And that’s what John’s Gospel wants to say to us too: in this new creation inaugurated by Jesus heaven and earth have met together and touched each other, for the Son of Man has been raised up to be in his own body the ladder that has joined them together. This is indeed creation with a difference! The old creation was marked out by separations and divisions: taken to extremes in the Gnostic reworking of the story. But the new creation is marked out by the removal of the middle wall of partition. And it is this new creation that has become the location where we tentatively, fearfully, hopefully, are being called to discover what it might mean to respond to Jesus’’ follow me’ in our own time and place. In the incarnation of God in Christ the word became flesh, and through Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection God promises that the gateway and bridge between earth and heaven will never be shut. So the word continues to become flesh but it now becomes our mission, through and in the power of the Spirit, to become the pathway through which this truth is made real in our world.

In a few minutes time through our celebration of Communion, or Eucharist, we are going to remember and join with Jesus and his friends in sharing that breakfast on the beach, that sacrament of new creation. In our speaking of words and eating and drinking of bread and wine, we will be living out what it means to proclaim the word become flesh. And what will we, must we, do when we leave this act of worship to be disciples of Christ’s mission in our world? Listen to Bishop Tom Wright as he gives us his answer:

The word became flesh, said St John, and the Church has turned the flesh back into words: words of good advice, words of comfort, words of wisdom and encouragement, yes, but what changes the world is flesh, words with skin on them, words that hug you and cry with you and play with you and love you and rebuke you and build houses with you and teach your children in school.

…So Peter there is work for you to do. You are going to leave the fish business, which you know so much about; you’re going to leave it for good, and you’re going into the sheep business instead, which at the moment you know precious little about. I want you to feed my lambs. I want you to look after my sheep. I want you to be you, because I love you and have redeemed you; and I want you to work for me, because out there, there are other people that I love, and I want you to be my word-become-flesh, my love sitting with them, praying with them, crying with them, celebrating with them. And how can you do it?… Peter, don’t just tell them in words. Turn the words into flesh once more. Tell them by the marks of the nails in your hands. Tell them by your silent sharing of their grief, by your powerful and risky advocacy of them when they have nobody else to speak up for them. Tell them by giving up your life for them, so that when they find you they will find me. And Peter, remember: follow me.’ (© Tom Wright)