The lectionary blog for this coming Sunday focuses on the ‘Gospel of the Palms’, Luke 19.28-40. But the liturgy of Palm Sunday moves quickly from this moment of apparent triumph to Jesus’ suffering and death only a few days later, events which are of course also our focus on Good Friday. Next week’s blog will reflect on the meaning of the crucifixion and will take as its starting-point the challenge of ‘Peace in heaven?’ that is presented by Luke’s Gospel of the Palms.

Clare Amos, Director of Lay Discipleship, clare.amos@europe.anglican.org

Luke’s account of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem has got the capacity to bring out the pedant in me! Because if you read the biblical text carefully, Luke 19.28-40, you will see that Luke’s Gospel, unlike the other three, nowhere mentions ‘palms’ – or any other kind of greenery. So, in the years when Luke is the lectionary gospel, should we in fact be referring to ‘Palm Sunday’? In truth, I am perfectly well aware that there are more important things to worry about – especially at the present time! But it is an indication perhaps that Luke’s account of this crucial episode in the life and ministry of Jesus has some significant difference of emphases, when compared with the other three Gospels. Luke’s account somehow feels slightly less ‘triumphal’. For example, the word ‘Hosanna’ also doesn’t actually appear in his narrative – though the word is prominent in Matthew, Mark and John.

Conversely Luke’s is the only account of the episode in which the word ‘Peace’ appears (Luke 19.38). It’s not there in the other Gospels. In Luke’s account the name ‘the Mount of Olives’ is also more prominent at the heart of the story, ‘As he was now approaching the path down from the Mount of Olives’ (Luke 19.37). Given the age-old association between olives and peace I think this may too be significant. It also of course builds a connection with the agony in the garden that Jesus is shortly to endure – since the name of this garden, at the foot of the Mount of Olives actually means, ‘Olive press’ (Gethsemane).

Luke 19.41-44 are not part of the lectionary Gospel. There may be good reasons for this, but in some ways it is a pity, since these verses, which speak of Jesus weeping over Jerusalem, continue the theme of ‘peace’ which has been introduced just above. ‘If you, even you, had only recognised on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes’ (Luke 19.41-42). Jesus’ words include a deliberate ‘pun’ on the name ‘Jerusalem’, the city which has ‘peace’ (shalom) in its very name, but which has patently often not experienced ‘peace’ throughout the millennia of its existence.

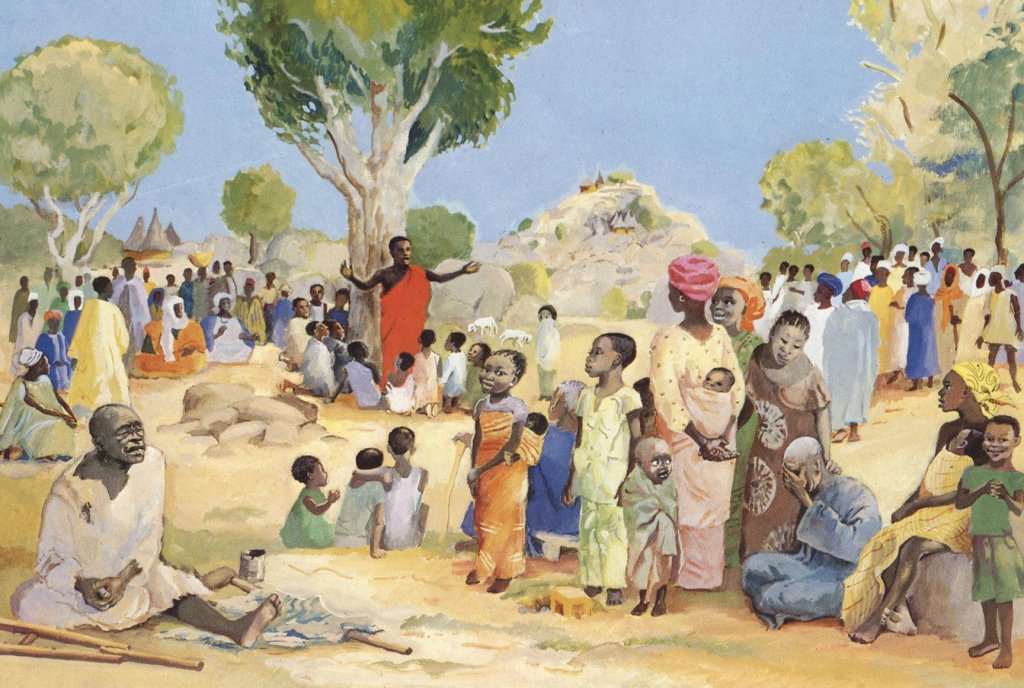

The continuing use of the motif of ‘peace’ in Luke 19.41-44, encourages us to go back and look more closely at the first time it appears in the story, in Luke 19.38. It is part of the cry of ‘the whole multitude of the disciples’ as Jesus begins to descend the mountain towards the gates of Jerusalem:

‘Blessed is the king, who comes in the name of the Lord!

Peace in heaven, and glory in the highest heaven!’

What is fascinating (but rarely noticed) is that this is the counter-point of the message sung by the angels at Jesus’ birth,

‘Glory to God in the highest heaven,

And on earth peace, goodwill among people’. (Luke 2.14)

So the angels of the nativity sing of peace on earth, while on ‘Palm Sunday’ the disciples sing of ‘Peace in heaven.’

Who got it right, the angels or the disciples? I owe the following thought to a reflection originally offered by Fred Kaan in Wisdom is Calling. Kaan comments:

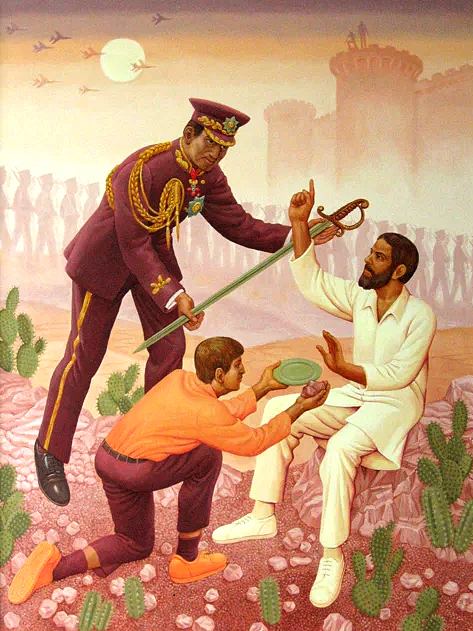

[The song of the disciples] ‘is a completely crazy and total misrepresentation of what God had in mind from the beginning. The angels sang, ‘peace on earth’. The followers of Jesus sang, ‘peace in heaven’ – many of them still do, whereas we should be on the side of the angels. Peace in heaven is none of our business. As earthly disciples we should not waste our imagination and emotions on envisaging peace in heaven, because we are human beings inhabiting ….[the earth] which we are called to fill with the Father’s glory’.

Given the lack of peace at the present time in our world, and especially in our continent of Europe, this is a salutary observation. To focus on ‘peace in heaven’ is certainly diversionary, but it can also be potentially dangerous. In my experience of working in interreligious relations for the Anglican Communion and the World Council of Churches, a theme that I have frequently found myself focusing on is that of religiously motivated violence. I think it is not too much to say that there can be a connection between wanting everything to be right ‘in heaven’, and taking violent steps ‘on earth’ to enforce our religious ideals. And it is not just an ‘issue’ for non-Christian religions. Certainly there is increasing (and I think justified) reflection at the moment about the ‘religious’ component of the Russian motivation for the attack on Ukraine. For some at least of the Russian leadership, both religious and political, their actions may, in a distorted sort of way, be an attempt to enforce ‘peace in heaven and glory in the highest heaven’.

And if the ‘multitude of the disciples’ on that first Palm Sunday got it wrong when they sang ‘peace in heaven’, then that perhaps helps to explain the otherwise puzzling comment of Jesus at the end those verses which have described his weeping over the city. Jesus suggests the pain that Jerusalem and her people would suffer was due to the fact that ‘[you] did not recognize the time of your visitation from God.’ (Luke 19.44) On the surface at least those who sang with a loud voice to welcome Jesus to Jerusalem, did ‘recognize’ their visitation. But was it perhaps that their singing of ‘peace in heaven and glory in the highest heaven’ presented a challenge to ‘peace on earth and goodwill among people’, and did not really comprehend the vocation of the one who came to be ‘Prince of Peace’? Is this why the pain of Jerusalem, that beautiful, and ‘competitively loved’* city, has cried aloud in its stones for the last two thousand years and we can still hear its sound of suffering even today?

* ‘competitively loved’ was a phrase often used of Jerusalem and the Holy Land by Bishop Kenneth Cragg, Anglican bishop, poet, specialist in Christian-Muslim relations and friend.

(The blog for the coming week will continue to explore the theme of ‘peace’, linked to Jesus’ crucifixion, and reflect on how this event at the heart of our faith may indeed link peace in heaven and on earth.)